BMD: A True Contender TTRPG

If you want to gun down contemptible aliens—annihilate as many as possible, on a massive scale—then the game I’m working on is right up your alley.

This game is something I’ve been waiting on for a long time. Unfortunately, no one stepped up to the plate. “If not you, then who? If not now, then when?” I’m biting the bullet and making this vision into reality.

The Basics

BMD is an ultra-pulp far-future universe where aliens have conquered and enslaved humanity. You play as a troop leader, commanding part of a scattered renegade force intent on opposing the demonic alien menace. Billions Must Die, a call to arms to crush the enemies of Terra.

Revenge, the re-assertion of Terran superiority, the pathway to a thriving future for mankind—all common reasons for joining the Sol Crusaders. Led by a figure known as the Prophet—a man whose awakened psionic ability manifested as future-sight—the Crusaders are intent on one goal: the total annihilation of the enemy.

But to accomplish that, war must be waged—war on an unprecedented scale and from a uniquely disadvantaged footing.

Take back territory. Undermine alien strongholds and influence. Terrorize their populaces. Rescue and recover Terrans—and add them to your ranks. Lofty goals all, but how can they be accomplished?

Begin by building up forces. You and a dozen of your like-minded buddies is a good start. For talent like yourself, the Prophet will give his blessing of funds and special equipment.

Research labs, cyberprison centers, power distribution stations—whatever your preferred style of trouble, assemble the right teams with the right tools for the job.

Raw force not your style? Use your spy network to identify important local officials and send psions to assassinate them. The mining station’s alien chief of security? Mindcrushed. The planetary governor’s sudden “heart failure” can cause enough chaos to lower alien response capability planet-wide, making room for someone with a more robust platform to have a go.

Maybe covert assassinations, long-term psyops, and underground recruitment don’t appeal to you. Just steal a freighter and crash it into the colony’s life support array; the null atmosphere will take care of the rest. Shoot down anything trying to leave the spaceport—simple! Of course, you will need to achieve orbital superiority. But after that, every single one of the demons will be dead; hundreds or thousands or even more.

And with every dusted alien, your legend grows. Infamy among the enemy is the clearest expression of your power. “Insurgent”, “terrorist”, “asymmetrist”—these names are just an indicator of how much they fear you. As your Infamy grows, you will factor more into their precautions. It will become more difficult to operate in the shadows, but you will inspire ever more true-blooded Terrans to join your cause.

Make no mistake, there are plenty of things that will stand in your way:

enemy militaries and security forces

the dangers and difficulties of space travel

alien technology, numbers, and logistical strength

the disunity of conquered Terrans

But with the pride and spirit of good men; the backing of a leader that can glimpse the future; and a little Atlantean supertech, you can overcome those odds. Drive back the alien, take his lands and conquests, destroy him, and declare his mass grave a triumph for the Crusaders.

If you are successful, you will inevitably gather even more men wanting to fight for you. Build outposts, strongholds, and ships for them—or steal it all and use the enemy’s weapons against him! Don’t wait around for the war to be over; make your move and win it all back.

One Goal, Three Keys

BMD can only work when three foundational elements actively support one another: the character and combat systems, the worldbuilding systems, and the metafiction.

The combat system is familiar territory for TTRPG players. Its role is to define how forces, small and large, can interact and what the outcome of those interactions can be.

To wage a war is to consider territory, resources, the local factions involved, the disposition of enemies, and much more. Having a discoverable gameworld allows scouting, exploration, intelligence, and setting/game knowledge to have meaningful impact on play. The worldbuilding system is aimed at delivering a complex, sensible gameworld by means of repeatable procedures that are easy to follow.

The metafiction, or “history,” aspect sets the tone and expectations for how other game systems can work and provides all entities with a consistent underlying structure of allegiances and motivations. The historical relations between Terrans and their enemies, who these enemies are and what drives them, and particular canonized events which comprise the literary “setting”—these elements are not a story, they are a conceptual starting point for the story of your gameworld.

I. Character and Combat System

(A much more detailed look at this is available in the BMD Development Blog)

The outcome of many conflicts is a certainty—and for these, no game mechanics or dice rolls are needed. But when there is uncertainty involved, BMD rules provide an organized way of allowing participants to mutually discover and direct outcomes.

I won’t focus too heavily on the combat system—the worldbuilding system is where the most exciting features live—but I want to outline enough to give a sense of how it “feels” to navigate the resolution mechanisms.

Though these systems may seem new or unusual, novelty is not the aim. The procedures and mechanics have been designed with particular goals in mind, and some of those goals (e.g. fine-resolution vs. scaling) are in tension. Solving these issues required some new approaches.

Conflict Resolution Overview

The BMD character and combat system is not simplistic, but it is a simple design.

When an attack is being made, there is an Attacker and Defender—each with a sensible array of scores that give us information about their capabilities. The Attacker’s goal—in a game mechanics sense—is to create as much Damage as possible. The defender allocates, absorbs, and resolves Damage.

This resolution system is used at every scale of combat, but it is a bit abstract without an example situation. Consider the individual soldier scale:

A Terran soldier has an Accuracy (ACC) score. His weapon grants him Coverage (COV) and Lethality (LTH) scores. He may have other equipment that acts as a modifier to these scores.

When making an attack, he performs an Accuracy test (1 die roll). If he succeeds, we look to his weapon’s Coverage score. For a weapon with Coverage 3, he will roll three Lethality tests (3 dice). If two of these Lethality tests succeed, he has generated 2 Damage (DMG).

On the defending side, we have the need to allocate Damage.

A lone soldier receives 8 Damage from an attack. His combat suit provides 3 Protection (PRT). The first 3 Damage allocated equals his Protection (he is “saturated” with Damage), triggering a Toughness (TGH) test. The next 3 Damage equals his Protection, triggering a second Toughness test. The remaining Damage is insufficient to trigger a third Toughness test.

The soldier passes one Toughness test but fails the other. He loses one Hit Point (HP) per failed Toughness test. This HP loss is the pathway to elimination from the battlefield and to various considerations including wounds, healing, and structural integrity loss.

By default, damage allocation favors the defender in BMD. This means the defender can place that damage as he wills, consistent with the rules. Some circumstances would favor the attacker, however—e.g. Damage from a sniper would be allocated to favor the attacker, signifying the sniper choosing a priority target.

In summary,

a) Attacking

Roll for Accuracy. Roll a few more dice if you succeed—and the sum of the resulting successes is Damage.

b) Defending

The Defender receives and (typically) allocates a pile of Damage, weighing it against Protection to see whether he needs to make Toughness tests.

Scaling

A resolution system is more useful if it can scale to all the conflict sizes that player characters and NPCs would pursue. The example above allows us to imagine what is essentially a duel between two Terran soldiers at the infantry level.

In BMD, player characters will be expected to control a force of ~10 figures from the outset—even at the lowest Infamy levels. Let’s examine this scale of one squad vs. another.

For clarity, a figure is a single individual—a single person or entity. A unit is a cohesive collection of figures acting as one, generally united by a command structure.

Example: Terran unit vs. a small unit of Garm

On the left, we have an attacking squad of Terrans. There are 9 soldiers plus a leader, making 10 attacks → 10 Accuracy tests. Six Accuracy successes provide a total Coverage of 18 (here their weapons all have Coverage 3). We yield 13 Damage from Lethality successes.

On the right, we have a defending squad of wolf-like mutant Garm consisting of 12 ratgarm (1 HP) and 3 garm alphas (2 HP)—all with Protection 2. One of the allocation rules is that Damage must be allocated to an unsaturated figure before a saturated figure. With Protection 2, it takes 2 Damage to saturate any of these defending figures.

The defending player decides to allocate to all three garm alphas first, placing a total 6 Damage to saturate them and then a total of 6 more to saturate three ratgarm. The last point of Damage will be harmlessly absorbed by the armor of a fourth ratgarm.

Because the ratgarm have 1 HP, he rolls their Toughness tests first for simplicity—two fail and are eliminated. Two of the garm alphas also fail their Toughness tests. But because they still have HP remaining, they are not necessarily eliminated. One fails a Wound roll, becoming eliminated by severe injury; but the other succeeds and continues the fight with 1 HP remaining.

Figures eliminated from the battlefield are exposed to injury and possibly death, but this will most often be an after-battle consideration. Figures with high HP can keep fighting until their HP reaches 0, but every HP loss comes with a small risk of elimination.

Resolve and Morale

During the course of a campaign, a unit’s cohesiveness, readiness, and willingness to fight can vary. Resolve is a measure of the spiritual vigor of a unit, the effectiveness of its commander, and the level of its morale. Resolve can be lost in a variety of ways but can also be managed by skillful command and strategic personnel management.

Every unit has a Full Strength (FS) rating, derived from the total number of Hit Points in the unit. A unit in combat will perform as normal until its remaining Hit Points is less than or equal to its Half Strength (HS)—its FS divided by 2.

When a unit reaches HS, the actions available to it become more limited and it must make a Morale check before declaring actions for the round. It is likely to lose actions, make a hasty retreat, or otherwise become much less combat-effective.

Victory in large engagements will often be a matter of reducing units to Half Strength by causing enough HP loss with high amounts of Damage.

Movement, Initiative, and More

There is a great deal more that I would love to talk about (especially equipment and vehicles like starships and landing craft), but these are mostly elements that provide support for the principles implied by the combat resolution details given here.

II. Worldbuilding System

The defining feature of a well-designed TTRPG is its ability to hold a coherent gameworld. The gameworld is more than just a place; it’s embedded with the reasons for characters to exist and the rules by which those characters discover, conceptualize, and pursue their aims.

One of the principal design goals of BMD is that it offers a way to construct, inspect, and modify—through player actions—a rich gameworld. It is my intention that this covers every aspect of the world, from the distant void of space to boots on bloodstained grass.

1. Star Sector Generation

BMD campaigns take place in isolated “pocket universes” called star sectors. These clusters of activity in the Milky Way galaxy act as places to center the unfolding story of the Crusade against the alien menace. Starting out, let’s consider the campaign to take place in a single star sector.

Star sectors are represented as a 10×10 hex grid. Each hex signals an occupied star system (orange outline), “empty” space (black), an anomaly (blue triangle), uncharted space (purple background), or some combination.

The immediately relevant places are the occupied star systems (orange). Occupied systems have planets, moons, or space stations that are already well-established. These strategic locations, or Locations, are the key to all activity in the game—so how are they put together?

We begin with the star itself. The type of star tells us the system focus: Habitability, Materials, or Energy. This is a distributional notion; a Habitability star won’t necessarily have a Location capable of sustaining high population, but that is a more likely result than with the other two star types.

Then we determine what number of Locations are in that system, and we discover class and attributes for each of them. Discovering the gameworld is a frontloaded activity, and generating static information for new Locations is the bulk of this work.

The image above is the essential outline. Within the star sector are (occupied) star systems. Within the star system is a set of Locations (pictured: a planet, a gas giant with orbiting moon, a space station). Each Location has a host of attributes; some are generated and others are derived.

SecLevels

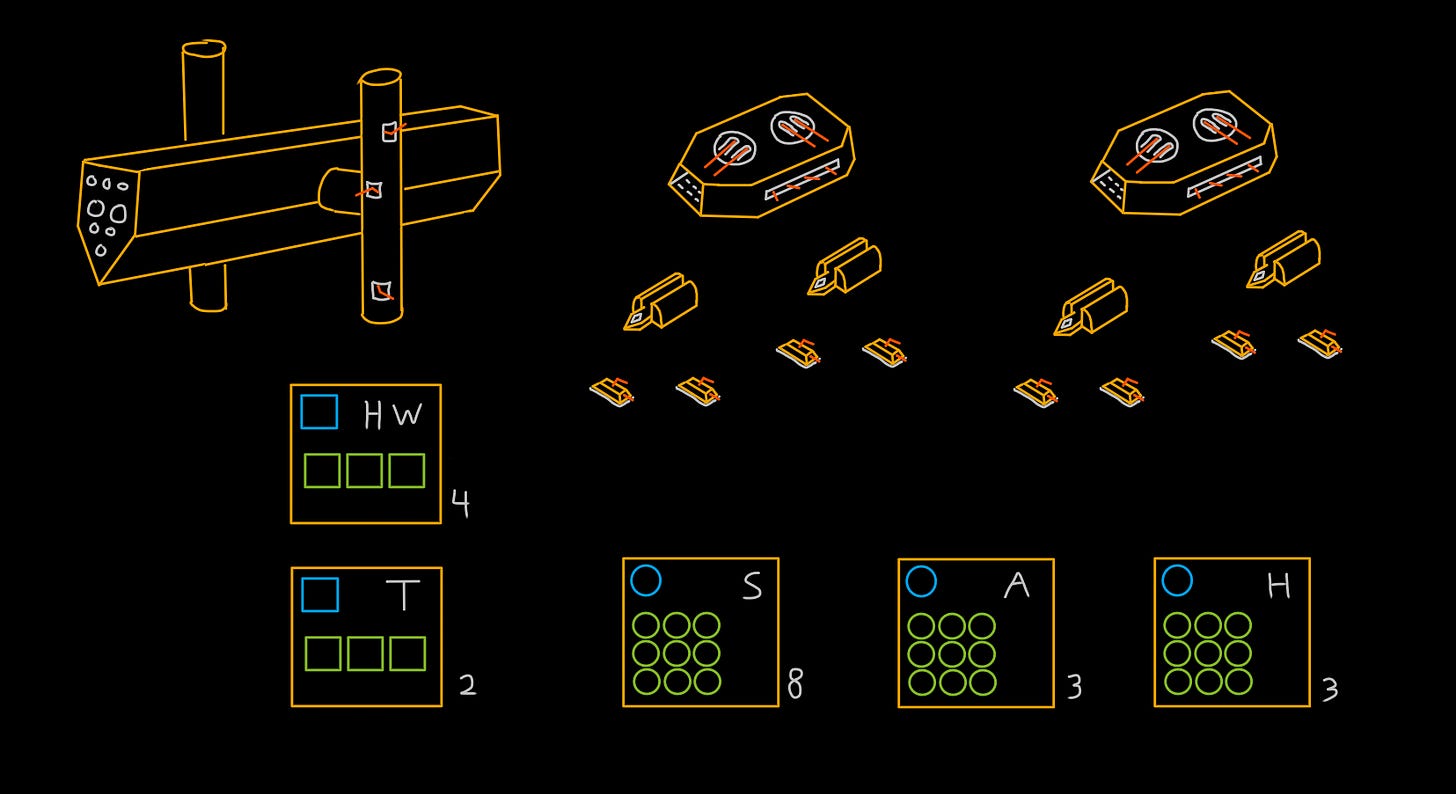

Security Level, or SecLevel, is representation of military and police presence available to that Location. A ruler of a SecLevel 6 Location can decide to drop to SecLevel 5 to immediately secure a standing army. Each faction has their own distribution of forces that comprise a SecLevel.

For example, a Terran SecLevel can be “spent” to muster 1 battleship, 2 warcruisers, 4 assault landers, and 8 ground transports (APCs). This equipment is fully staffed, loaded, and supported by logistics and command apparatus. The force comes with a combination of deployable units: 4 Heavy Weapons teams, 2 Technical specialist teams, 8 squads of Standard combat infantry, 3 squads of Assault infantry, and 3 Heavy infantry squads.

SecLevel is highly interactive. It can be lowered voluntarily by the ruler to “create” a significant military force. But it can also be lowered by opposition incursions that weaken security, organization, and logistics. A ruler can “absorb” a large military force to raise the SecLevel of a Location.

Because military power and SecLevel can be exchanged, a ruler can lower the SecLevel at Location X, send the resultant military force to Location Y, and “absorb” that military force to raise the SecLevel in Location Y. By this method, both defensive and offensive power can be concentrated with simple planning and tracking.

Influence Centers

Each Location has at least one Influence Center (IC). Every IC has SecLevel equal to the Location’s “global” SecLevel. If all ICs are captured—even if only for a moment—the opposition becomes the new Influence (owner) of the Location.

Thus, defending and attacking ICs is a central mechanism of advancing the war.

Consider a player character, Gunnar, who wants to conquer Sterrata, a Size 6 moon. The moon is represented by the 6×6 grid of Transit Zones, or Zones, above. Gunnar has information about a High-Value Target (HVT) at a Weapons Research Lab (IC) in Zone A1. If Gunnar can get a team to A1 and successfully eliminate the HVT, the moon’s SecLevel will drop by at least 1 from the chaos. More damage is possible if the IC is sufficiently compromised during the Encounter.

Let’s assume Gunnar has the option to land in any Zone on the moon. His objective is to reach A1, trigger an Encounter, and eliminate the HVT during the Encounter. There are many possible routes he could take, but let’s look at two.

Gunnar has 3 infantry squads—a very small force built for stealth. Landing and Zone transit are actions which trigger possible Encounters. The difficulty and complexity of these Encounters depends on the Zone’s SecLevel. Gunnar’s 3 squads cannot stand up to a full-blown SecLevel 4 response. Thus, being detected or having an alert trigger would be cause to abort and exfiltrate—mission failure.

If he landed in C1 (orange attack path), his force would be only two Zone transits from his objective. A 2-Sec is a risky landing, potentially triggering a confrontation where his landing craft gets shot down! However, his force is small and stealthy (a bonus to evading Encounters when transiting Zones), and this attack plan would only take two transits. The risk is front-loaded.

If he instead landed in A6 (purple attack path), his force is more than twice as far from the objective. However, landing on a null-Sec Zone is consequence-free—no risk to his landing craft! Additionally, both 1- and 2-Sec are very easy for his small force to sneak/evade through without incident. The downside is this path will take much longer (5 instead of 2 transits) and comes with the possibility for many more unintended Encounters on the way to the objective.

2. Encounter System

The Encounter System establishes the character and feel of Locations in our star sector. Anyone familiar with AD&D or ACKS already has an idea what an Encounter System entails, but let’s take a brief look at it.

Gunnar is on the moon Sterrata in a 1-Sec Zone. He transits with his force, choosing Evasive posture, to an adjacent 2-Sec Zone. For brevity, we will assume knowledge of several details. Terrain, equipment, force makeup, weather, and other factors affect transit time.

Evasive, Hunting, Rapid, and Basic postures all affect transit time and the chances of certain encounters. With Evasive posture, the likelihood of an Encounter decreases—but let’s assume the Encounter roll comes up positive.

Sterrata has several important attributes we need to know for encounters:

Influence: Yazimfa

PopType: Terran

Biosphere: Fauna

Now we build our Encounter “table.” We have slots numbered 1 through 10. They all default to Influence—so we have 10 slots of “Yazimfa” in our table. A step-by-step process, informed by the Location parameters and the SecLevel of the Zone we’re moving into, leads us from an initial result of

1-10: Yazimfa

to a final result of

8-10: wild

5-7: Terran

1-4: Yazimfa

Building this table “live” allows Encounters to accurately reflect the Zone and the circumstances of the Location. We roll a D10 to determine a result.

A “wild” result is the most complex because we must consult a Creature Creator based on Location attributes—unless we have a creature library for that location already available.

A “Terran” result requires a roll on the Terran faction table (referring to the SecLevel 2 column). Terrans could be allies, independents, or forces working with the enemy—rolling on their faction table will tell us which.

A “Yazimfa” result requires a roll on their faction table. Because they’re an enemy faction to the Sol Crusaders, the follow-up Reaction roll tells us how advantageous the Encounter setup will be (and to which party) instead of their diplomatic disposition towards Gunnar’s force.

After determining the disposition and extent of forces in the Encounter; which scenario template (if any) is applicable; and factors like Surprise, the Encounter can be gamed out. An extensive guide to setting up Encounters (including how to construct and organize interior spaces) is too much to include here.

III. Metafiction

The historical events and gameplay of BMD all take place in our own galaxy (the Milky Way galaxy). With the exception of Earth (known as Terra) and our star system (known as the Sol system), the star systems and their Locations are generated procedurally as described in section II.

Player characters (PCs) and their followers are part of the Sol Crusaders. This single faction dominates the gameplay and design of BMD. They are a small faction with limited but asymmetrically important resources.

The enemy factions (the Yazimfa, Dhross, and Vessamar races; and the minor Galactic Council races) are inaccessible to players except through referee-assigned wargaming positions.

Recruiting players to be enemy faction leaders and warlords can provide an intensity to the creative elements required to win battles and make progress on the war-fronts. Otherwise, the network of diplomacy between the Sol Crusaders, Terran independents, and these alien factions will provide a means to mechanically mediate strategic-level decision-making.

Referees are encouraged to take advantage of the Prophet’s position by providing his lieutenants with resources and overarching directives. These lieutenant positions, codified by the metafiction, are perfect for patron play—having players act out lieutenants’ schemes and interactions. These patrons seek to increase their own power and influence, competing with one another within the greater context of the Crusade.

The Prophet, an Ur-Patron

Because player characters (PCs) are all part of a single faction—the Sol Crusaders—in BMD, an ultimate source of support and leadership is a feasible design. He can see the future and act on his glimpses to further the Crusade. This is all mediated mechanically, and plays out as background effects on the campaign.

The Atlantean cruiser Thanatos, undisturbed for millennia, now spearheads the Crusade’s efforts. It was the Prophet who recovered it, who amassed a hoard of Atlantean tech into its vaults, and who used his insight to boil the Yazimfa ocean worlds in retaliation. It was he who showed Terrans that the war was possible and who submitted that the righteous were compelled to fight.

Having a trove of Atlantean tech, the Prophet is ostensibly the wealthiest individual in the galaxy—but he has no interest in the alien sphere as a market. The Crusade produces its own hard currency, the Invincible Sol Coin (ISC, pronounced issk), from Atlantean materials and backs each coin with services and goods few independent forces can provide.

But the Prophet is only one man. He concentrates mainly on the war and its progression. To this end, he bids his lieutenants seek out warriors of great potential—for they and their contributions will be needed to build and retain the coming Terran empire!

The Character Classes

The Hierophant

Burning flechettes whistled overhead, creating a wafting spray of blue-green confetti from ruined alien plants. The commander’s voice, unmoved by the sudden explosion of violence from our flanks, sounded out over the comm.

“Saith the Wanderer, Heed not the suffering they shall heap upon you. Though the enemy casts thee into prison, tortures the body and mind, covets the bold spirit in thy chest—heed not the fear of death, and I will grant thee a sword.”

Even through the stale tang of the rebreather, the smell of old leather seemed to fill the battlefield. I envisioned the off-white sheaves of paper splayed open on the primitive bound book he always carried. Rifle ready, I checked the calls—targets left and right.

“Saith the Warrior, I sought the Power and was heard; and the All-Might delivered me from fear. I asked the LORD, Who will bring me into the fated city? Who will lead me into the sanctuary of my forefathers' forefathers?”

Black silhouettes with misshapen crow-beak helmets dashed from behind terrain, heading further to our rear—encircling us. I tagged them and raised the rifle. Another confirmed my call, and red lines on the HUD formed a phalanx pointed at the black shapes—we were guns-on-target.

“Who will order my march and guide me to the killing fields? Who will lay the path for my steps into the principality of the Void?

“For the sword of the righteous smolders in the presence of evil.”

The Hierophant’s talents rely on Presence, instilling confidence and purpose within their followers. Hierophants attract high-morale troops in large numbers. They are the keepers of prized banners, constructed with Atlantean shielding technology, gifted directly by the Prophet so that men of spiritual wisdom can protect Terra’s warriors. Any man can potentially become part of an unbreakable triumphant force led by a Hierophant.

The Warthane

Cans of cold-brew spilled from the rough sack onto the table with a rude clattering. The commander flashed a loose hand signal, dismissing the air of formality and readiness we held and indicating it was time to partake. He popped his helmet and dropped his mask, testing the air as we shuffled past the table.

“Hit first. Hit hard. In that order. A Pterodar laser system’ll roast your whole landing crew in one swipe. But it takes five ‘Alpha Rally’s to acquire an’ fire. A single tungsten bead in the operator’s head will save all your skinny hides. Hit first.” He paused, bringing the can to his mouth.

“If you shoot out his knuckles, the Dhross can’t pull a club or a shield—it’s every bit as good as slicin’ his whole arm off. And the shield’s mostly a mind game. If they ain’t dead by the time they get close—well that’s why every man here is carryin’ incendiaries. ‘Cindis’ll solve your close-up threats.

“But sometimes you’ll see a commander with a big shield. That’s why we ain’t out here fighting one-on-one. Multiple units at mixed forward positions can spit intersectin’ fields of fire.” He choked the remainder of the can down, his right hand never leaving the rifle across his chest.

“Sometimes it’s a numbers game. They toss in artillery, you gotta scatter. You may get hit. If your brother gets hit, you save him. Medics, snipers, lookouts—any of us can get hit, but if everybody shows up to fight, ‘least five brothers got your back at all times. A big net don’t care ‘bout a few loose strands.” He ran his gloved palm over the sides of his mouth, soothing the mask marks.

“Birdman’ll give some of you problems—but that’s why we got different units. Tag ‘em on the helmet. Get on the comm. Throw a flair if you got to. Somebody somewhere in this outfit has got the solution to the problem.” Squinting, he peered towards the setting sun, checking it against the timer on his wrist.

“Better to be the guy everyone’s calling on for help, though.”

The Warthane is a born fighter, and an expert at leading and teaching men to cause maximum mayhem. Warthanes are men naturally gifted with a great intuition for causing destruction. Unmatched killing experts, the men they lead are a more sophisticated fighting force—organized and specialized for trouble. The Prophet supports the Warthane with the most devastating Atlantean loadouts so that these followers can fulfill their purpose as the vicious vanguard of the Crusade.

The Armacogitar

My heart pounded as the creature crawl-shuffled past. Never seen one before. Yazimfa. Underwater spider-things from hell. They appear, act, and move in a way that nature abhors, that turns the stomach. Every molecule in my body cried out to dust him.

But we needed to wait, let him pass, stay hidden. These storage containers would ensure he wouldn’t see, hear, smell, or taste any trace of us—but only so long as we kept them closed. He snap-wriggled only inches from us, but the commander’s potent Seeing made it worse—like my mind had its nose shoved in the Yazimfa’s mental swamp-stench.

The thing left. Several minutes passed. I saw, or probably felt—we all had our eyes closed in the darkness—the commander nod. Bishop pulled the latch and the box started depressurizing.

A dim green light shaded the storage room. Not good enough—we would have to switch to full-vis. As I reached to change helmet parameters, I saw—felt—what seemed like the whole facility. The commander was reaching out.

Putrid swamp masses scraped along a dozen hallways over four levels—reek unbearable. Wiry, purple pipes snaked their way across patrols. Probably Council forces. Red, boiling fountains—Dhross soldiers, without a doubt—marked the entry to a space that was more empty than emptiness. Psionic white noise. Pretty much guaranteed our target was there.

We all felt it at once, nodded to each other. Two levels down, one hallway section. We moved instantly, no hesitation. That’s what I like most about our unit—everyone on the same page. We turned, covered, advanced, and climbed down in a blink.

The commander burned two of the red fountains into my mind so that I couldn’t focus on anything else. I could feel the sweat building on my neck against the suit. Grimy, uncomfortable. Take care of it, he’s saying.

I did. Popped them both like grapes. The fountains went cold, then disappeared. Normally, I couldn’t get two at a time; that’s the commander’s doing.

Turn the last corner. Two huge Dhross. One is slumped against the wall; the other lifelessly goring the first’s midsection with a facial horn. Right side is clear to walk. I take cover behind the Dhross-pile on the left.

Switch to full-auto. Bishop’s on the door. Target is inside—with a traitor psion.

Smoke ‘em fast.

We all nodded, and the door swiftly swept into the wall.

Only Terrans can achieve psionic abilities. Only one in a hundred Terrans, when exposed to Atlantean devices called psi-crystals, display the gift. And among those few, perhaps one in a further thousand are capable of channeling—utilizing and enhancing the psionic abilities of others. These men, when identified, make dangerous commanders. When paired with other psion soldiers, the Armacogitar is an unmatched weapon who can turn the most terrifying Terrans into an unstoppable, ultra-lethal specialist force.

The Enemy

The Yazimfa

The director’s drooping trunk bobbed up and down, signaling confusion. With three sweeping tendrils, he shoved the holographic reports aside, allowing his speech digits to be visible so there would be no misunderstanding.

“If I am reading these reports correctly…” He paused.

“Yes, it is difficult to believe,” the amalgamyzer signed in response, his outer flaps thrumming to provide aurokinetic clarity in time with his statements.

“…the humans see things in the hyperplex. Despite the damage, they find it entertaining and will pay to be attached.” The director was appalled at the oddity.

“They call them dreams. Subjectively ultrarealistic hypothetical scenarios—reportedly with absurdities as premise,” the amalgamyzer supported. “The dream experience is addictive to them. They are excited to return to the machines upon exiting, despite the degradation inflicted.”

The director jerked his pincers about with agitated energy. “And they produce more quodules—not fewer. We’re absolutely certain of that?”

“Over two-hundred thousand times more per cycle. For every human subject, we could close two quodule mines. There are many millions of humans; even if we could only get several thousand—”

“We could crash the quodules market—after shorting it.” The director tapped pincers together in contemplation. “Show me the plans.”

The amalgamyzer’s maw wrenched open in predatory amusement as he assembled the collected reports.

The Yazimfa are a spider-like subterranean race with tremendous wealth owing to an invention that “mines” experience and imagination from sentients—the hyperplex. Aliens consume the mined quodules for creative inspiration—the essential source of all alien creative works.

Yazimfa were the driving force behind humanity’s enslavement. An addictive hyperconnected experience was sold to Terrans as a replacement for other kinds of networks—up to and including replacing their systems of governance. Even the most “free” Terrans that live under alien rule are mined through ubiquitous requirements to “plug in.”

They are the most hated foe of the Sol Crusaders. Years after the Hyperplex Fraud—when billions of Terrans were enslaved as hyperplex miners through a years-long scheme—the Prophet plotted primarily against the Yazimfa, managing to foment war between them and their former servants, the Dhross. He used this opportunity to lay waste to thirteen ocean worlds they called home.

The Dhross

Twenty in plain view, forward arc. Half with weapons facing.

So small. Weak. Pathetic creatures. Any real soldier would magma dive if he felt an ounce of fear from these.

Four legs cry out—charge! Bring up the shield, give a great throaty bellow; the horn of the elderblood sounds, and the pack follows. The rock trembles.

One swipe of the club would crush three—no, four—of these stringy humans. They’re slight and feeble; they probably clutch one another in fear like side-eyes.

Stampeding forward. Five Dhross warriors against these twenty pathetic saplings. Thunder in the blood, in the air—thunder! This charge will prove our seedworth—the Matriarchs will continue our line.

Buzzing bites. Pain. A warrior falls. Blood. But the shield will hold. Trust in the shield.

A gnaw in the eye. Blinded. But I can hear the charge, feel their fear. I will not stop until they are still and silent.

The Dhross are truck-sized triceratops-like predators. Simplistic and aggressive, their warrior caste make up the vast majority of their population and function as competent violent manpower. Serving as the proposed police replacement for Terran worlds, the Dhross warriors were used to enforce social quarantines and quash violent resistance.

They are despised by the Sol Crusaders as slavish servants of the demonic alien order—unthinking violent action bred to follow evil.

The Vessamar

“Only eighty-seven quodules up to this point.” His slim digits stretched idly, sending an undulating diseased-gray pattern gliding across his upper wingspan. Being forced to look up at the overseer caused a rising tension in Vriinak’s upper torso. He let the bottom of his beak droop to ease the pain building beneath his shoulders—the core of his attached wings. The slack-beaked appearance he gave off was part of the intended humiliation.

The overseer flexed his own shoulders, causing his false-blue wings to snap the air briefly. This overt display of satisfaction at his underling’s discomfort was considered a Key Motivating Factor by bureaunology. He started, “That’s almost twice the daily lim—”

“Yes, yes,” seethed Vriinak, seeking a pivot from this punishing conversation. “Limit rescinded, pre-interest well-established, forward-paid, bureau-assured. My private funds.” He looked down at his console, snapping his beak comfortably closed. Relief flooded through his shoulders. The overseers responded to energy. He needed to be convincing.

Another twelve quodules rounded him off to a pleasing ninety-nine. Seat injection was best—pleasant and fast-acting. He wouldn’t suffer quodule burnout like the others; he had stronger gene therapy than that.

Beak nearly to his chest, down-staring the console, Vriinak’s wings stretched as he reached to the outermost controls of his station. His digits pulled, tapped, and pressed with machine precision as his mind raced to recall and recombine the unassembled project elements.

“Extended vassalage from the plan adds seventeen sub-route possibilities. Nix these three, fourteen subs. From these subs, ninety-one extra Commodities Of Note. Forty-one ‘mods high-prio—arbitrage rating blue.” Vriinak preloaded the next set of figures.

The overseer’s spotted beak swatted dismissively rightward, and he gave a lethargic hiss. “These chains of—”

“Taking into account Project Hyper, missed prediction of available complex neurological tissue—casualty estimates lower bound four millions humans—eight millions optical nerve tree—seventy-three percent dorsalous therapy success—”

Vriinak violently slapped the zoom control, bringing a single chart into focus. His beak snapped upward imperiously, and his wings struck outwards at his sides. “Four thousand percent return.” A smug mirth twittered through his throat-complex.

The overseer outstretched his right-side digits, flashing his wing in surprise. “Interesting catch! Impressive!” He held his breath in reflection. Praise came naturally to him in his shock, though it was against protocol.

Vriinak’s twittering halted suddenly. Something missing. The gleam of his triumph vanished. His beak snapped back towards his chest, and he down-stared with a severe demeanor. His digits went to work as his mind raced.

“Subs logic mistaken! Trace a new major route through these seven. Time-corrected recovery rate minus fuel… and these three stops—negotiate for berthing, secure possible live specimens from Corrections/Infractions for regeneratives research—as much as…” He stopped suddenly.

His beak slacked open as he looked up once more at the overseer. “As much as seventeen thousand percent return.”

“No… it can’t be,” protested the overseer.

“Yes, it is.”

The ever-dying winged Vessamar hold a vice grip on life through a twisted combination of gene treatments, cybernetic replacements, and “recycling”—the cannibalizing of their own and other species for healthy organ tissues. They have unmatched technological prowess and logistics expertise, and they have the fastest and most efficient transport ships.

Their role in the Hyperplex Fraud was simple—replace all Terran logistics with their superior equipment and management, only to cut off access at the crucial moment. Between the Vessamar’s monopoly on travel and the Dhross enforcers, the aliens’ strategic victory over Terran worlds was assured.

Other Enemy Forces

The Galactic Council consists of hundreds of (minor) alien races who, both individually and collectively, are largely pawns of the big three (Yazimfa, Dhross, Vessamar).

The Garm are a notable enemy force of non-sentient hivemind aliens. In a catastrophic runaway process of active self-mutation, they evolved from a particularly obnoxious species of vermin on the Dhross homeworld after being introduced to other, richer environments.

They are a consuming force, evolving to digest and extract energy from the planets they assault. When a Garm force senses a Location’s resources are expended, they form a sophisticated biological warp catapult that launches an invasive biomass at their next target.

Parting Shots

Anyone playing BMD rules-as-written (RAW) is working towards the same goal, in a general sense—the elimination of the aliens, corresponding with the conquest of a star sector by Terran forces.

But everyone playing BMD with the same backdrop star sector has the same exact goal as everyone else—the conquest of that star sector by Terran forces. This allows many tables to simultaneously participate in the same war in the same star sector, making the war into something much larger than just a Thursday-night gaming meetup.

I see TTRPGs as existing in unnecessary stasis (or decay, if we include more modern entries). Historical wargames are mostly purpose-made to model specific scenarios. Battle systems like Warhammer and its brethren have moved beyond that—but only slightly. I want to see TTRPGs re-absorb their wargaming heritage and move on to becoming something bigger than they’ve yet accomplished.

I want to see games centered around massive (but not fully specified) worlds in constant motion, involving many actors and events that necessarily collide. This world creates scenarios which must be carefully gamed out because adversarial participants want to see a resolution. The tools for gaming out those scenarios are simply provided by the game rules.

Even though I’m not certain BMD can fully achieve all these goals, it is a big step in that direction.

Supporting the Game

You can support the game’s development most directly by becoming a paid subscriber here on Substack. I will still be doing the usual stuff—occasional game design articles, podcasts (they’re coming), and ACKS campaign log. Those things will remain freely available.

This game is getting put together, tested, finalized, published, and printed regardless of what happens. I’m committed to putting these ideas out into the world, and I am convinced that TTRPGs need the push it will provide.

However, your direct support absolutely will hasten and ease its development. It’s a strong justification to allot focused time. Additionally, I need to support the editors and artists who will really make the final product a worthy piece of craftsmanship unto itself.

If you directly support this effort, you will get a PDF rulebook when the game is published. In addition, you will have access to highly detailed development articles here. These are a means to give supporters a close-up view of designing and perfecting the game, where I demonstrate specific problems and the various methods I use to reach a satisfying and well-aligned conclusion.

I’m excited to finally share this project with others. You can help by subscribing and sharing! Thank you for your continued interest and support!