BMD: Encounters

The heart of the gameworld

(A huge thanks to my readers—men of refinement, gifted with impeccable taste—and especially to the brotherhood of heavy hitters that decided to support BMD by becoming paid subscribers. This select group of aristocratic key-keepers shines with a handsome radiance, providing a Promethean fire to power the benefits of this blog.)

The fundamental character of a TTRPG can be found through its gameplay and systems. When do we roll dice and why? What is glossed over, and what is given intense focus? What are the underlying assumptions reflected?

In BMD, fixed elements like places on a map, the gravity strength of a planet, and the nature of a specific weapon are anchor points for within-world reasoning. These elements of a game’s rules provide depth in space, allowing us to presume a consistent set of facts that apply anywhere across the gameworld.

Encounter systems give a gameworld depth in time. Activity, motion, and events are constantly taking place at multiple levels of abstraction—it is the encounter system’s role to convey their workings and character in a way that players can leverage.

The Role of Deep Space

Most gameplay activity takes place in Strategic Locations (i.e. Locations). But these are in star systems with identifiable distances between one another. Even though Locations are the dominant active spaces, they are not isolated!

If we are carrying out long-term operations on an enemy-owned Location in System B, there is little stopping them from sending reinforcements from System A. With advanced Vessamar transit drives, a trip from A → B might take as little as 48 hours.

Since we can travel across space, it is natural to have Encounters there. Enemy (or friendly) fleets, environmental hazards, and bizarre occurrences are unusual but certainly possible in the void between stars. The Encounters that happen as a result of space travel are different enough to deserve their own treatment in another context.

In this article, we will instead focus on what happens when our characters traverse Locations.

An Example Location

Consider the planet Redwood1.

Influence: Dhross || PopType: Terran

Size: 6

SecLevel: 4 || Influence Centers: 2

Atmosphere: Breathable || Biosphere: Fauna || Gravity: Balanced

PopSize: High

Redwood is a Terran-populated world ruled by the Dhross—a great target for the Sol Crusaders. “Breathable” means the atmosphere is the right mixture of pressure and gases for natural habitation by Terrans; Dhross require “Basic” atmospheres and will need equipment and infrastructure to make up for this.

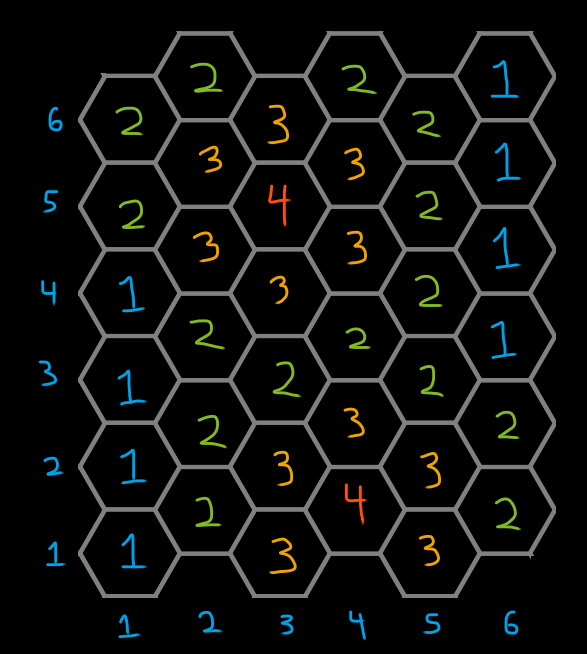

The two Influence Centers (ICs) rolled were a population hub [3,5] and a training camp [4,1]. Redwood’s SecLevel is 4, establishing a baseline value at each IC.

A coherent gameworld has dynamic aspects and static aspects. Sometimes these aspects are contextual. Redwood’s gravity and SecLevel are two “facts” that create a coherent fixed structure of behavior across the entire Location; in this way they are static.

But the SecLevel is subject to change by interventions. Significant sustained attacks could lower it, while a significant effort of reinforcement could raise it. In this way, some planetary characteristics act as both dynamic and static depending on the questions we’re asking.

The Encounter System is the workhorse that accounts for and supports these ideas. But when does an Encounter happen? What are the mechanics behind it?

Rolling for Encounters

There are two types of Forces to distinguish here: provisional and persistent. A provisional Force is “created” when an Encounter happens; these conceptually exist in the gameworld as a result of activity in the Location. A persistent Force is the type commanded directly by player characters2. Persistent Forces are not “summoned” up and are not the result of circumstances or chance meetings but have a well-tracked “complete” history of presence and activity.

With this distinction clear we can ask: when do Encounters happen? There are two cases.

Encounters happen when two persistent (opposed) Forces meet. The details are determined by the intersection of a few systems, but it’s enough to know that the rules conspire to have two persistent Forces Encounter each other—even if one is trying to evade the other.

The second case is the most typical and comprises the bulk of the Encounter System. When a persistent Force executes a move across Zones (hexes) in hostile territory, they roll for an Encounter.

A Persistent Force in Motion

Assume we have a Troop Leader (TL) and his corresponding Force at our disposal. Our lone Force travels across a Location’s Zones, declaring postures and destinations with each step.

Evasive, Hunting, Rapid, and Basic postures all affect transit time and the chances of certain encounters. Evasive, Rapid, and Basic postures are different styles of avoiding Encounters. Evasive is the most likely to avoid and Rapid the least likely. The Hunting posture is different—it guarantees an Encounter of some kind.

Encounter rolls establish three facts: the terrain, the provisional Force, and the Response. But it only triggers if the Encounter is not evaded.

0. Encounter Evasion

If we’re Hunting, we are guaranteed an Encounter (but not necessarily the one we’re after). Using any other posture, the roll we make is an Encounter Evasion (EE) roll. The [Basic, Evasive, Rapid] postures each require a result of [5+, 3+, 7+] to evade before considerations of other bonuses.

The size of a Force is an important factor for EE. For example, Forces that are [Very Small, Small] get a bonus of [+2, +1]. Thus, a Small Force under [Basic, Evasive, Rapid] posture would need [4+, 2+, 6+]

The Resolve3 of a Force is also an important EE factor, along the same lines as size.

A Force that has Resolve: Bold (+1) and size: Small (+1) would get an overall +2 bonus to Encounter Evasion. This means our [Basic, Evasive, Rapid] postures require a result of [3+, 2+, 5+]. Note that we can’t do better than 2+. If this Bold, Small Force made an EE roll with Rapid posture, any result 4 or lower means we failed to evade—an Encounter occurs!

1. The Terrain

We executed a move in hostile territory and failed to evade an Encounter. The first step is to determine in what environment the Encounter will take place. We roll D10 and consult the Location’s terrain table. Each Biosphere has its own default distribution of terrain. Some effects can change a Location’s natural terrain, and this would be reflected when the Location is generated—not during play.

Note the important implication that Zones do not have a single associated terrain! We might pass through the same Zone and have an Encounter in two different environments therein. This has many implications beyond the scope of this article.

2. The Encounter Type

Now we roll D10 on the Location’s Encounter Table to determine the type of Encounter. Usually, there will be three such tables, corresponding to Low/Medium/High SecLevel. Here’s what one of those tables might look like for Redwood.

8-10 Terran

5-7 Wild

1-4 DhrossHow did we get this table? What exactly do the results mean? We’ll return to these points—the main thing is that it’s a simple D10 roll to determine the type.

3. The Response

A Response roll is similar to a Reaction roll in traditional TTRPG designs. We roll 2D6 to find the Response.

Result Enemy Terran

2 Ambushed! Hostile

3-5 Disadvantage Unfriendly

6-8 Balance Wary

9-11 Advantage Friendly

12 Ambush! AllyBecause of factional realities, the Sol Crusaders never have anything but hostile relations with alien forces. In such cases, the Response roll is telling us about the circumstances of contact—who saw whom first, and how quickly did both sides react?

Encounter setup is a strongly prescriptive system with particulars of scale and deployment options. To summarize, having “Advantage” in Encounter setup amounts to choosing deployment advantage or initiative advantage. An “Ambush!” result means we get both benefits. The corresponding negative results give these advantages to the enemy Force.

If the Encounter type is “Terran,” we come back into the realm of uncertainty in relations. A “Hostile” result means another Response roll, treating the Terrans as an enemy Force. Other results provide an insight into diplomatic questions. “Unfriendly” Terrans might report your movements to local authorities, for example.

The Logic Behind Encounter Rolls

From the gameplay perspective, we’ve established how to make Encounters happen (almost). Let’s now look at some of the system details behind the design.

Terrain

Since we’re using a prescriptive system of Encounter setup that involves deployment of Forces at scale, the terrain tells us what kind of modifying features we can expect to see and how densely they are distributed along the battlefield. This includes everything from obstructions like buildings or rock faces to various forms of cover.

Knowing the terrain provides creative players with an ineffable quality of information they can use to reason about their circumstances. These terrain considerations are particularly important in non-random Encounters where Forces can be dug in or are assaulting a reinforced position.

Encounter Type Tables

Earlier, we saw an Encounter table, but where does it come from? What do the results mean? It’s easiest to explain by working through an example.

Consider a Force on planet Redwood at [1,3] moving into [2,3] with Basic posture—normal speed, normal chance to evade—and no modifiers. Based on the speed of the Force, this move will take 4 hours.

Over the course of this 4 hours, our Force tries to evade other Forces. To see if we were successful, we make an Encounter Evasion roll at 5+ because of our posture. We fail to evade, rolling a 3.

We roll for terrain: forest. We go to roll for Encounter type but it looks like the referee left the Encounter tables blank accidentally! It’s fine, though, because we can easily figure out how to build them ourselves.

First, every Encounter table conceptually starts with 10 Influence entries. Redwood has Dhross as the Influence faction.

1-10 DhrossThen, we check for Wild results. If the Biosphere is Fauna or Flora, we add 1 Wild. If Megafauna, we add 2 Wild. Redwood is Biosphere: Fauna.

If Influence and PopType are not the same, we add 3 PopType results. Redwood has Influence: Dhross and PopType: Terran. We add 3 Terran (civilian) results.

Then we look at SecLevel tier for additions.

[0,1,2] Low

[3,4,5,6] Medium

[7,8,9,10] High

Lowsec adds 2 Wild. Midsec adds 1 Wild. Highsec adds 1 Influence. The Zone we are moving into is at SecLevel 2—thus, we add 2 Wild.

So far, we’ve added the following results:

3 Wild (1 from Biosphere, 2 from Lowsec)

3 Terran (from Influence/PopType mismatch)

These results get added to the “top” of our ten Influence results, giving us the following table:

8-10 Terran

5-7 Wild

1-4 DhrossAnd we’re done. We roll our D10 and see which result we get on this table.

Garm Invasions

The Biosphere of a Location won’t change, and the Influence/PopType mismatch also won’t change unless the Location changes hands. The only real “variable” is what SecLevel our Force is traveling into: hence, we need three tables for Low / Medium / High.

These tables can be jotted down when the Location is generated, meaning we won’t have to go through the exercise of figuring it out.

Unless something crazy happens—like a Garm invasion. The Garm are a feral hivemind type alien that launches biological meteors at target planets to infest them, soak up their resources into the biomass, and then launch that biomass at the next target.

In the case of extraordinary events like a Garm invasion, we’ll need to modify the “fixed” three Encounter tables—by adding 3 Garm results in this case.

We’ve talked at length now about “adding” results which are replacing Influence results. But what do the results mean?

Faction Tables

There are really only three categories of result in these constructions: civilians, military forces, and wildlife. Other categories (like Garm) are unique and have their own associated rules.

Wild results draw from the Location’s library of wildlife. If the library is “empty,” a creature creation system will provide wildlife Encounters based on Location attributes.

Civilian and military forces draw from the Faction Tables.

Let’s say we rolled a “Dhross” result. We go to the Faction Table, looking for the column corresponding with the SecLevel we’re entering (2) and roll D10. If we roll a 6, we encounter a Force “Platoon 1.”

We rolled a “Dhross” result, so we find the “Platoon 1” description under the Dhross faction. This description tells us the exact makeup of the Force in question—how many units, how they’re Organized (their weapons and troops), how many officers and which variety, how many of which types of vehicles, and so on. From this we have a complete understanding of what is encountered.

The same is true if we rolled a Terran result. We go to the Faction Table and look at the “Civilian” column, rolling D10. If we get an 8, we know to look for the Terran version of “Civilian Expedition.”

The Faction Table is designed so that the threats provided increase with SecLevel. The Civilian column is a notable exception—Civilian results can vary a lot regardless of the local SecLevel.

The different factions have notably different results on the Faction Table. These differences reflect their different combat doctrines and their particular physical, psychological, and economic oddities.

In the future, we will examine the Faction table results in more detail. To understand Encounters, we need only know that a “Platoon 3” is a stronger, better-equipped Force than a “Platoon 1” and that each faction has their own versions of these Force categories.

The Path to Mastery

The Encounter system is designed to be easy to use during play. We establish terrain, Encounter type (where we refer to the Faction Table), and Response. These points of information fill in the gaps for us and let us set up Encounters in an abstract theater-of-the-mind confrontation or as a tactical deployment with a well-specified scale and detailed understanding of the battlefield (the rules specifically allow for both).

But, as we have seen, BMD’s Encounter system has a strong emphasis on its inputs. To elite players these inputs are opportunities to intervene, to bend the odds in their favor. Mastery of the Encounter system is really about the interplay between knowledge and strategy—something that planners and schemers will appreciate, especially when we get around to exploring the intel system.

The Encounter system really is the crank that keeps everything else in the game turning. As testing continues, we will contemplate this and other as-yet-unexplored elements of BMD.

See more detail on how Locations are generated in the Outline of Play.

Much more about player Forces in Characters and Forces and the Outline of Play.

Resolve and Morale explains this concept in more depth.