Things have been quiet on the publication, lately. Invisible development workloads silently soak up time and attention. We’ll tide over the wait by using some of that work as a basis for a game design analysis piece.

First, a quick look at rulebook progress.

First Blood Trajectory

The early-look First Blood1 edition of the BMD rulebook is in intensive development. We are practically aflame with excitement for the release, and the testing process has been highly successful at eliminating would-be headaches and unnecessary friction.

For a game envisioned and designed from scratch—drawing from a unique mix of foundational antecedents—great care is needed. Making a BX derivative is not trivial, but constructing a game from first principles intended to bridge the gap between classical wargames and AD&D is the kind of project that most developers of sound mind would hesitate to begin.

Accepted Challenge

Moving from notes to a completed rulebook has been the best development decision thus far! It’s worth repeating: assembling answers to playtest questions from notes is reasonable when prototyping, but having an authoritative source of information forces designs to finalize and reveals contradictions and subtle tensions that no player should ever grapple with.

The vision for BMD is thus: a True Contender TTRPG that can stand among AD&D, ACKS, and Traveller in providing a complete system—a game that is a worthy arena for player mastery. This vision puts us in a no-compromise stance for development. When a problem arises or a new gameplay formalism must be defined, we are obligated to find smart, robust solutions. Competing with these juggernaut games demands nothing less than our best work.

Putting together the rulebook is an organizational (and technical) task that has its own difficulties, but creating a True Contender ruleset brings out tough design problems. We have been working at a fiend’s pace to diagnose and solve these issues with no compromises to the game’s final integrity.

Your patience will be rewarded! In the meantime, let’s detail some examples that the dev testing process has fixed and discuss a common refrain in design issues.

Player Interface vs. World Model

A pattern has emerged from designs that needed revisiting. Systems imagined (and executed) as ‘player interfaces’ tend to cause problems down the line.

A ‘player interface’ is a tool or functionality that is accessible primarily by the player controlling a canonical player character2. This kind of design is unintentional, an unconscious borrowing of techniques or patterns from more limited games.

This can be a subtle issue because canonical player characters (simply, PCs) are standout characters from both the gameworld perspective as well as the real-world perspective. Since the PCs are special, would they not necessarily have special events and outcomes available to them?

It’s easy to fall into this trap.

As an example, suppose the referee hands out “revive cards” to each player at the table. A card can be expended to revive the player’s character during the session. This is a clear example of a player interface—it’s intended as a benefit to the player rather than the character. Confusing the delineation between player and PC is at the heart of player interface problems.

It’s true that the character benefits from reviving, but the benefit has no apparent source and no interactivity! We lose diegesis and bring the solidity of the gameworld into question.

Player interfaces ultimately lead to video game logic3. Though they seemingly benefit the player, their presence damages player autonomy by degrading the World Model—the accessible and discoverable attributes and “internal logic” of the gameworld. Thus, player interfaces exist in inherent tension with the gameworld and the World Model.

Proclamation vs. Actuality

Couldn’t we design the gameworld to properly accommodate an example like this revival card benefit? Of course!

If we say that it’s a benefit to the PCs from the gods, it becomes RAW. But for it to truly be part of the World Model, it needs to be understood and acknowledged in the gameworld. There must be a category of gameworld characters who are aware of its existence. This awareness would affect their decision-making. After all, on what grounds does someone oppose a person who is revived upon death? Those who oppose this divine gift implicitly must oppose the giver! Opposing a divinity has implications about the nature of these characters.

Working through these considerations shows the substantial difference between a player interface and a system that properly supports the World Model. A throwaway one-liner saying “give your characters a card so you can revive them once per session if they die!” doesn’t do the job. It fails to satisfy the constraints implicitly imposed upon the gameworld.

Because this is a problem of degree where many examples are subtle, let’s highlight some specific cases from BMD development.

Resolve → Loyalty

We previously discussed Resolve4 at some length. The idea behind it is simple: Resolve is a reflection of the readiness and willingness of men to fight after stress, waiting, starving, and/or casualties have taken their toll.

Resolve’s design was a subtle form of player interface. It was mistakenly envisioned as a carrot-and-stick combo to get the players to “behave” and to reward them for good behavior. This is a reasonable notion, but making direct behavior moderation systems is moving away from diegesis and the gameworld—away from the World Model.

When we apply the concepts of Resolve to NPC forces, we find insidious confusions. When the players encounter an enemy force, what is that force’s Resolve? If the Resolve was very high (or low), wouldn’t they have been dramatically more (or less) successful in their patrols? The NPC forces “spawned” by the encounter system never interact with the Resolve system except by affecting the Resolve of the player forces.

Testing Reveals All

If PCs repeatedly retreat or face high Casualties (or both), their Resolve drops; when the PCs gain victories and spread the wealth to their fighting-men, their Resolve can increase. But what of the alien forces? If the aliens are beaten back, with rout after rout, there should be some correspondent effect!

Resolve is a measured attribute of a Force—a collection of units serving under a specific commander. If a Force routs, why are we tracking its Resolve? Surely they would disband the Force and reorganize a different one if things got too bad.

That’s the next problem. When PCs reorganize their Force, we run into a Ship of Theseus question where it is unclear how many units or figures must be swapped out of a Force before it becomes a different one. And what if the units in the Force are reorganized but only to change equipment? What if the Force Commander appoints an acting commander? Does that affect the Resolve? Why or why not?

This was a frustrating concept in testing—a sign that something important was off course.

The Resolve system brought about more questions than it answered, and it consistently resulted in confusing attempts to reason about outcomes. But eliminating this system left gaps.

Filling the Void

If a faction attempted to form a spy network within a foe’s ranks, we used the target’s Resolve to inform the success of the attempt.

These ideas are in fundamental tension with one another, however. Resolve is a Force-level attribute. Forces consist of units—which consist of individual figures—led by a Force Commander. The faction player attempting spying correctly intuits that turncoats are formed from the weakest links. Resolve, as an attribute, lumps the entire Force together into an aggregate.

Smearing everything into an average hides strength and weakness—a misalignment.

When we scrapped Resolve, we were left with a sizeable gap in the design space for answering these questions.

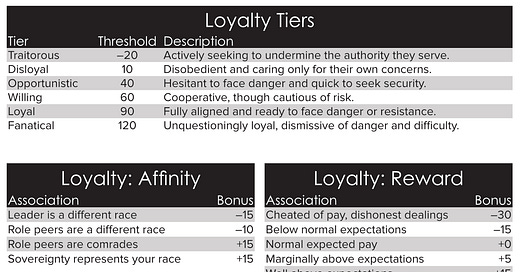

Loyalty Tiers and Scores

The answer to all these concerns (and more) is the Loyalty system. Anyone familiar with AD&D already has a good handle on how this system works, though it has subtle differences to suit BMD’s particulars.

A figure’s Loyalty has two aspects: a Tier and a Score. Loyalty is always measured toward a Sovereignty, such as a government or political faction.

The Loyalty Score (LS) corresponds with the Loyalty Tier (Tier). For example, LS between 40 and 59 marks a figure in the Willing Tier.

Figures only have their Loyalty checked in situations such as when:

ordered to perform a task under imminent threat of death

approached with a bribe or threatened for information

entrusted with the care of items of substantial value and portability

confronted with an extreme threat on the battlefield

In other words, Loyalty is only checked in exceptional circumstances! To do so, we roll a D100, aiming to achieve the Loyalty Score or less.

If unknown, figures begin with a base LS of 50, adding bonuses based on their circumstances. Mechanically, it’s very simple, but the answers it provides are clear and satisfying.

This system undoes all the problems with Resolve and brings strong utility, compactness, and additional benefits:

no persistent Resolve tracking → easier and faster gameplay

where Resolve was unintuitive, Loyalty is highly aligned with player expectations and the World Model

Loyalty is an individual concept—not a Force-wide or even unit-wide one; it’s very easy to aim and evaluate relevant questions

LS can be determined on the spot—no need to remember or record it

Loyalty is equally usable for the PCs, neutrals, alien factions, and anything else we could imagine

For example, if the players find neutral hirelings, the hireling Loyalty to the Sol Crusaders will be less than that of converts or volunteers. If the Dhross conscript a population of Vessamar into an emergency militia, determining their outlook uses exactly the same system!

The Loyalty Tier provides a way for us to reason qualitatively about a figure’s feelings and behavior, but it also links directly to quantitative outcomes.

Overall, it’s a dramatic conceptual simplification. Whether we’ve got a number implying a category or a category implying a number range, we can use the system from both directions to reason about outcomes.

Excavating the Resolve system, though painful, was a substantial upgrade in usability and comprehensibility for the player. From a design perspective, the World Model is much better supported by Loyalty.

Armor Penetration and Parallel Attacks

An important aesthetic goal of BMD is providing a futurized facsimile of contemporary weapons tech revolutions. This distinguishes the game’s combat feel and provides the rich array of full-spectrum warfare to be enjoyed by strategy enthusiasts.

In WWI and WWII, (infantry) body armor was essentially worthless! Ballistic power was relatively so strong that we routinely sent men to fight in little more than fatigues and winter jackets5. But today, there are production personal protection plates that can mitigate a black-tip .50 BMG round!

Research and background knowledge suggests that body armor, though it can always be defeated, will become increasingly relevant. Fighting-men of the future are more likely to resemble full-kit samurai than flight attendants. These predictions are reflected through BMD’s damage and protection systems.

Defeating Armor

It follows that Armor Piercing (AP) is chief among the weapons tech in BMD. Unfortunately, its original design performed below standards. In this implementation, AP X would treat a target with Protection X or less as 2. For example, AP 5 would treat Protection 4 as Protection 2.

It was neither complicated nor confusing, but the outcomes it created were frequently brought into question. Edge cases felt unsatisfying. The design did not ultimately achieve its goals.

“Specialist” Roles

Changing tracks, uniformity is used in BMD for simplification so that complex circumstances can be parsed and resolved with ease.

The most important such uniformity is the design of the infantry unit, a collection of individual figures that, ideally, all share the same equipment and fighting ability. To encourage this uniformity, BMD uses a concept of a Standard Weapon:

The Standard Weapon must be wielded by a majority of the unit’s figures. If no clear majority weapon can be chosen, choose the most represented weapon and use its Coverage score but decreased by 1 (to a minimum of 1).

If we have a full 10-man squad where 6 of 10 are using a LIRaC (Light Infantry Rail Cannon), then all 10 of them are treated—for the purpose of combat resolution—as wielding LIRaCs. Whatever the other 4 are actually wielding becomes irrelevant because the squad attacks as one body.

But we need room for exceptional circumstances. If a tank comes along, we want the guy carrying the anti-tank gun to have his weapon acknowledged!

The informally designated “Specialist” concept was envisioned as a means to allow for these fighters to be in a squad yet still work as a team.

And, naturally, this created havoc with the aforementioned Armor Piercing design.

The Big Problem

The subject is complex, but we can illustrate the main issues with an example.

It is important to understand the roles of Accuracy (ACC), Coverage (COV), Lethality (LTH), and Protection (PRT). A refresher on the 3-step attack resolution:

Accuracy Step: Roll

P[figures count] +ACC. Each success is a Hit.Lethality Step: Roll

P[Hits × COV] +LTH. The number of successes is Damage.Damage Step: Tally the Damage; the total is the Damage pool. Place the Damage pool on the target (to be resolved by the defender).

The pattern P[D] +B describes a dice pool with ‘D’ ten-sided dice (Power ‘D’) rolled with a bonus of ‘B.’ P3 +4, for example, is three D10s that succeed on 6+ (default success is 10+ results).

Attacking Unit: a squad of 10 Terran soldiers

9 of them are using LIRaCs

a “Specialist” is using a Nitro rifle loaded with expensive armor-piercing rounds, lending him AP 3

Defending Unit: a squad of unspecified figures with Protection 3

Consider the result that we achieve 5 Hits in the Accuracy Step—4 Hits from LIRaCs and one from the Nitro.

The anatomy of our attack is:

Lethality Step:

P[5 × 3] +4or 15 Lethality dice at 6+Assume 7 out of 15 are successful → 7 Damage

9 men are contributing Brutal 0.5 → 4 Damage added, for a total of 11 Damage

1 “Specialist” is contributing AP 3

Since the defending figures all have Protection 3, the defender would typically divide the 11 Damage by 3. This threatens 3 HP. But how does AP resolve here? Let’s go through the short list of naive solutions and the problems they have:

The whole attacking unit benefits from AP 3. This will be threatening 5 (11÷2) enemy HP.

Because one guy brought some armor-piercing ammo, our entire attack barrage over the round is treated as AP 3. That doesn’t make gameworld sense, even as an abstraction.

The unit gets no benefit from the one guy with AP 3. This will be threatening 3 (11÷3) enemy HP.

This is slightly more forgivable as an abstraction, but what if there were two such guys—or three? Creating a hard binary of value doesn’t solve a problem or answer a question. The circumstance creates the question in the players’ minds; saying “just ignore that” is unsatisfying and wasteful of the instinct to wonder and reason.

Because one figure has AP 3, one target will have their effective Protection reduced to 2 while the others are unaffected.

While this may satisfy some kind of quantitative balancing instinct, this isn’t modeling anything! Attacks in BMD are made by units against other units. The details of which bullet flew from which weapon simply don’t come into play at this scale. It’s fighting both the fundamental design and the intent behind that design.

“Specialists” Replaced

To be a special snowflake attacker one had to gain the Specialist trait somehow. Because this was mediated through randomized trait tables, it was not guaranteed to have access to a guy for using a one-off weapon. The “Specialist” tag is non-diegetic; it is basically video game logic and was (unconsciously) treated as such until it came under close scrutiny.

To move forward, we ask, “if one member of the squad is coordinating in a less-than-optimal way with the remainder, what would it look like?” The solution is two-fold.

Solo Attacks

Some circumstances demand that a squad member momentarily break from coordinating to fulfill a special role. The anti-tank weapon is a perfect example—the gunner essentially drops out of the squad, becoming his own distinct unit for the duration of an attack.

With a Solo Attack, the anti-tank gunner makes an attack separate and distinct from the squad. The remainder of his squad doesn’t need to plink their small-arms fire at the tank and can choose another target. In addition to losing the gunner’s attack contribution, the squad suffers an overall loss of 1 die from the Lethality pool in the Lethality Step of their attack to represent that small drop in coordination.

Parallel Attacks

Sometimes, a squad member will carry and use a weapon distinct from the unit’s Standard Weapon but still operate as part of the unit. As an example, a strong reason to break from uniformity is if a figure has an inherent Accuracy bonus—the Standard Weapon uses the squad’s lowest Accuracy score.

In a Parallel Attack, the figure is using a different weapon but must share the same target as his squad. When making a Parallel Attack, the figure resolves Step 1 and Step 2 separately, but adds their Damage to the unit’s Damage pool in Step 3.

Just as with Solo Attacks, each figure making Parallel Attacks causes the greater part of the unit to suffer an overall loss of 1 die from the Lethality pool in Step 2.

AP Redesigned

Ultimately, the way that AP functioned—whether with the “Specialist” design or with Parallel Attacks—caused confusion. A rule to clarify what occurs can resolve these questions in a legalistic sense, but it won’t necessarily reduce confusion for the players.

For the new design of AP, we changed it structurally from a binary effect to a Protection-matching scheme governed by a table. We let go of the idea of forcing simplicity onto the mechanic and framed it as “how can we reflect the nature of armor piercing weapon systems to correspond with real-world examples?” The very first attempted solution worked well and brought more than we bargained for.

Put in Practice

For each Accuracy success scored by a figure with Armor Piercing, a number of Lethality pool rerolls is acquired. Recall the attack resolution scheme:

Accuracy Step: Roll

P[figures count] +ACC. Each success is a Hit.Lethality Step: Roll

P[Hits × COV] +LTH. The number of successes is Damage.Damage Step: Tally the Damage; the total is the Damage pool. Place the Damage pool on the target (to be resolved by the defender).

Now our scenario, assuming 5 Hits, looks like:

5 Hits with weapons of Coverage 3 → 15 Lethality dice (6+)

we subtract 1 die for the coordination penalty from the single Parallel Attack, leaving us with a Lethality pool of 14

7 out of 14 are successful

Because 1 Hit contributed AP 3, we look at the table and see we get 1 Lethality reroll!

We reroll one of the 7 failed Lethality dice, expending our reroll. It succeeds!

8 out of 14 successful Lethality dice → 8 Damage

9 men are contributing Brutal 0.5 → 4 Damage added, for a total of 12 Damage

Since the defending figures all have Protection 3, the defender divides the 12 Damage by 3, threatening 4 HP.

A Hidden Bonus

The new design (Lethality pool rerolls) happens in Step 2, whereas the old design (Protection check) happened after Step 3. In the old design, the defender would have to track the Damage amount and modifying factors such as AP. With the effect of AP already built into the Damage pool, the defender can go back to recording simple Damage amounts.

This tightens the reins on accounting but also makes it easier for the defender to allocate Damage when the time comes. They need only know the scores of their own figures. Though subtle, this is a significant speedup in combat resolution.

A More Typical Example

Suppose we have a squad of 10 Nitro wielders using AP 3 ammo. Their targets all have Protection 3.

Accuracy Step: From

P10 +4we yield 5 Hits.Two of our misses were 1s → Reliable lets us reroll 1s. One is converted into a Hit, giving us a total of 6 Hits.

From the AP 3 column on the table, these 6 Hits lend 6 Lethality rerolls in the next step.

Lethality Step: We start at

P[6 × 3] +4From this Lethality pool of 18, we yield 8 successes, initially.

Rerolling 7 of the ten failures gives us 4 more successes → 12 Damage!

Damage Step: No additional unit-wide offensive traits are in play. We yielded a total Damage pool of 12.

Because the defender’s figures are all Protection 3, this attack threatens 4 (12÷3) HP.

Diegesis Shows the Way

Mechanics take a backseat to game procedures, but mechanical mishaps put the brakes on play sessions and could be indicators of larger problems. It’s easy to get caught in the hamster wheel of swapping out mechanics if one doesn’t work, but it’s better to take off the designer hat and adopt the diegetic perspective—get to the root of the problem!

Putting the focus back on the World Model benefits everyone in the long run. Even issues that seem like minor mechanical headaches could be interfering with players adopting the in-game mindset. Guard your game well!

Thank you for your readership! Primeval Patterns thrives on the basis of the sincere interest and support of hobbyists like you.

Liked the article? Some other interesting things:

Follow the author on twitter.

Check out BMD, a far-future wargame-infused TTRPG about slaughtering aliens. See the latest intel on the war.

Think carefully when designing or using skill systems!

Understand starting an ACKS campaign from scratch.

With work, we can achieve TTRPG Supremacy!

If you are a true fanatic, take the oath of battle and become a paid subscriber here on Substack. This directly supports the war effort (and the development of BMD plus the design research on this blog.)

BONUS: paid subscribers can read extensive BMD development blogs and are guaranteed a PDF copy on BMD’s release!

An in-depth examination of character roles includes the idea of the canonical controlled character.

Video game logic devalues and contradicts player autonomy. Diegesis provides the perspective to defeat VGL. Simulationism is the tool to achieve diegesis. This is the summary contention of Unlocking TTRPG Supremacy.

It’s worth pointing out that helmets and head gear saw substantial developments, though.

It's cool to see the process as these changes are made, and that you're willing to make sweeping changes when coherence would call for it. Well worth delaying First Blood to have these sorts of things intact, a good call IMO.

I am curious on the AP table, it appears that it's generally better to have an AP rating equal to the defender's armor, rather than higher being better. Does this require the attacker to know the defender's armor rating? Is this done in an attempt to model "weapon vs AC" as armor proceeds from body armor to tanks?