Resolution Systems, Part 1

The mediator between 'plan' and 'campaign canon'

Every TTRPG takes inputs from players to produce outputs into an ongoing campaign. The greater TTRPG sphere loves to discuss dice mechanics, class levels, and rules exceptions—but the design principles we use to build resolution systems are rarely addressed.

Let’s view a commonplace campaign occurrence from multiple perspectives to demonstrate the presence and nature of a resolution system’s architecture.

Praise be to the patrons of Primeval Patterns who make this publication possible! Prestigious princes of proficiency and philosophy, all!

Kings and warlords combine their strength, supporting the march to WAR! Take up your sword, subscribe, and make your mark—our work is supported only by brave men like yourself! Loyalists joining the vanguard will receive their just rewards—victory, PDFs of BMD releases, and the undying glory of righteous battle!

Scenario: Simple Murder

The campaign has evolved. Subtle misalignments in the goals of powerful, influential characters have developed into red-hot points of conflict. Put plainly, Gregor wants Wilson dead.

The character of focus is the assassin tasked with killing Wilson. Whether out of loyalty to Gregor or simple professionalism, our assassin is determined to collect his fee.

Wilson, who usually spends his days holed up in his personal keep, is attending a high-society evening party at a foreign estate; this is our assassin’s opportunity. He studies the grounds and local area in preparation for the night of the event.

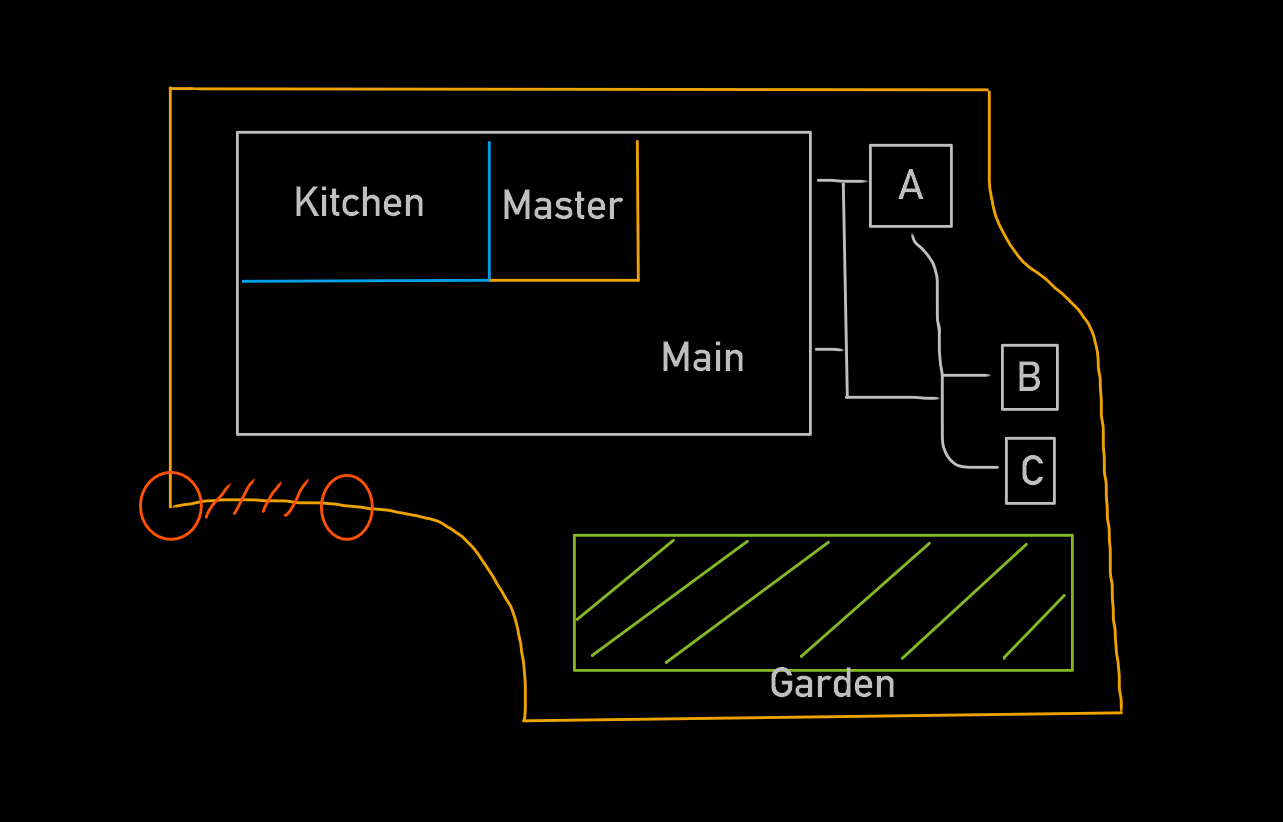

The estate is surrounded by walls; a gate is the only entrance. Points ‘B’ and ‘C’ are supply sheds unlikely to attract guests, but point ‘A’ is a gazebo perfect for drinks and quiet conversation. The shrubbery garden could be a zone of interest.

Due to the inherent properties of the TTRPG, this scenario could play out in an unfathomable number of ways. But for instructive purposes, let’s see how two different styles of resolution handle two different assassination plans.

Attempt 1: Conventional Play

The conventional approach to these scenarios is to work the material into the atomic level1. That level is where the resolution mechanisms of modern designs live.

We convert our sketch into a square grid. When the event night approaches, the referee will usher the assassin character into the “scene.” He will be placed on some grid square and proceed to footstep from that point.

The controlling player of the assassin has formulated two distinct plans that follow a different logic, and he begins to analyze those plans in light of his grid placement somewhere outside the walls.

Stealth Plan

The first plan focuses on entering the estate unseen:

Climb the wall from outside

Set up a rope (to be pulled down by a nearly invisible thread) to rapidly climb back up when necessary

Climb the wall down (no rope yet)

Hide until an opportune moment, particularly for the target to visit point ‘A’

Surprise backstab with a poison dagger

Mad dash to the rope

Sprint to escape the estate

This plan is a grid-walk from outside the wall to behind the storage sheds and then another grid-walk from the sheds to the gazebo (and one more grid-walk for the escape).

Because the assassin’s controller has such a detailed plan, it is easy for the referee—who is well-versed in conventional play idioms—to assign the tasks to skill checks. Climb check on the outer wall (1). A check to set up a rope fixture (2). Climbing down (3) and making a stealth check to avoid notice (4). Sneaking from the storage sheds to the gazebo (5). Hiding long-term at the gazebo (6). Surprising the target (7). Resolving the surprise attack (8). Hiding once more (9) and potentially dashing to the rope if unsuccessful. Lastly, perhaps a bonused climb check (10) and a substantially bonused hide check (11) to escape the estate.

Each of these rolls is predicated on the success of the previous, and we can already see a problem. If this assassin character has an astonishing 90% success chance for all these checks, we can mark out what his ultimate chance of success will be after successive rolls in the sequence:

90% → 81% → 72% → 66% → 59% → 53% → 48% → 43% → 39% → 35% → 32%

As the assassin makes his way along the series of tasks, his overall chance of failure looms larger. Players experienced with this resolution style have an intuition for this phenomenon without ever having to calculate it. For such a highly skilled assassin to have so small a chance of overall success for a simple kill seems wrong. Players will take this as an indication that this plan is bad and and that more successful methods must be available to them.

Disguise Plan

The assassin’s controller constructs a second plan:

Disguise as a servant

Fetch a dish from the kitchen

Poison the dish and/or drink and serve it directly to the target

Hide in the garden or near supply sheds

When an opportunity arises, climb stealthily over the wall or dash through the gate

Since analysis of the Stealth Plan led to the conclusion that more actions → higher chance of failure, the assassin’s controller decides on a more compact plan.

The referee, in his familiarity with the conventional play resolution, will detect that the compactness is a strategy to increase success chance. He may even view this as an unfair or exploitative abuse of the resolution style, depending on his taste. This is where doubt can creep in—where his duty to keep play faithful to the rules will collide with the ambiguities inherent in conventional skill systems2. “How many rolls should there be? What is fair?”

Getting back to the grid, our disguised assassin begins at the gate. Will his disguise work? Depending on the system, he may roll a Disguise Check or the guards may roll a Perception check, or some combination of the two. In a vacuum without any rules, the case could be made that the “bypass the gate guards” task is resolved by a single check, but many systems imply that each guard and staff member at the gate would get a chance to see through the assassin’s disguise. This ambiguity floats around many conventional systems, making the referee’s decision that much harder.

Then if the assassin passes his Disguise Checks at the gate, he proceeds his grid-walk to the house. There may be more guards at the door, or he might pass through into the kitchen. Particularly if he is disguised as serving staff, our intuition is that the kitchen is the most difficult place to fool with disguise. Will this be handled by increasing the difficulty of his Disguise Check? Is the difficulty supposed to be handled by allowing each of the kitchen staff a roll to see through his disguise?

We expect a check for adding the poison into the food or drink. Hiding and climbing and dashing out of the estate are handled as previously established.

Which plan?

To compare expectations of success between the Disguise and Stealth plans, we would need to specify the number of required die rolls and their success rate. Determining these factors is difficult for reasons intrinsic to conventional play idioms—where the referee, acting as the World entity, ultimately determines how many rolls are made. This problem is exacerbated when skill systems are presented, to maximize generality of use, without the exceptional detail that is required for multiple rule-readers to independently come to the same conclusion.

But these are only surface-level problems. The root cause of the ambiguity and punishment of planning is seated deep in the core of the design. For contrast, let’s see another style of resolution.

Attempt 2: RAW AD&D

What happens when we try to interpret the same two plans but using the rich resolution systems provided by AD&D?

Assassin Concepts in AD&D

Let’s go piece by piece through pertinent passages.

Assassination

First and foremost, assassins in AD&D have access to the Assassination table by surprising a target. From the Player’s Handbook (PHB):

(pg. 29)

[Assassination] gives a roughly 50% chance of immediately killing the victim; and if this fails, normal damage according to weapon type and strength ability modifiers still accrues to the victim. … The assassin decides which attack mode he or she will use: assassination, back stabbing, or normal melee combat.

In the Dungeon Master’s Guide (DMG), we can see the story is more complex. The level of the assassin is compared to the level of his target and the chance to kill is given on a numerical scale from 0% to 100%.

For example, if the assassin in our scenario is level 9 and is attacking another character without class levels, he has a 95% chance to kill on assassination attempt! For that, he only needs surprise. There’s more as well:

(DMG, pg. 75)

The percentage shown is that for success (instant death) under near optimum conditions. You may adjust slightly upwards for perfect conditions (absolute trust, asleep and unguarded, very drunk and unguarded, etc.). Similarly, you must deduct points if the intended victim is wary, takes precautions and/or is guarded.If the assassination is being attempted by or in behalf of a player character a complete plan of how the deed is to be done should be prepared by the player involved, and the precautions, if any, of the target character should be compared against the plan. Weapon damage always occurs and may kill the victim even though “assassination” failed.

Not only is this crystal clear, but it even suggests and formalizes the format which we implicitly invoked and followed, with the assassin’s controller creating a plan of action to be evaluated. At many tables, conventional idioms would bring players and referees alike to draw a grid, start on a square, and improvise through the process by relying on atomic-level resolution—a method which clouds our ability to reason about possible outcomes.

Creating a plan (and a target’s counter-plan) before anything is set up implies a great deal about the options available for resolution; we’ll return to this point later.

Stealth

(PHB, pg. 29)

[Assassins] have all abilities and functions of thieves; but, except for back stabbing, assassins perform thieving at two levels below their assassin level …

Assassins gain all the abilities of thieves, with most at reduced level. The ones we need are Move Silently, Hide in Shadows, and Climb Walls.

The thief class abilities are especially relevant to our discussion because while their design was warped into modern conventional skill systems, they are a set of exclusive membership-only abilities in AD&D. If a character wants to hide, they will simply do so. But if a character wants to hide in what is essentially plain sight, they must be a thief (or assassin, in our case)! Thus, let us look closely at these abilities to guard ourselves against unconscious assumptions from conventional play experience.

For Move Silently, it is described:

(PHB, pg. 27)

Moving silently is the ability to move with little sound and disturbance, even across a squeaky wooden floor, for instance. It is an ability which improves with experience.

This is not like the “Stealth Check” in conventional skill systems. The implication is that anyone could move silently across quiet footing—and that someone without thief abilities has no chance of accomplishing silent movement across anything difficult. This is not “walking quietly,” but more like “gliding skillfully across loud tile floor in an echo-rich room without making a sound.”

(PHB, pg. 28)

Moving Silently can be attempted each time the thief moves. It can be used to approach an area where some creature is expected, thus increasing chances for surprise, or to approach to back stab, or simply done to pass some guard or watchman. Failure (a dice score in excess of the adjusted base chance) means that movement was not silent (see SURPRISE). Success means movement was silent.

And for Hide in Shadows, on the same page:

Hiding in shadows is the ability to blend into dark areas, to flatten oneself, and by remaining motionless when in sight, to remain unobserved. It is a function of dress and practice.

Anyone can hide behind a barrel or under a bedframe, but only a character with thief abilities has this advanced camouflage ability.

Climbing

Climb Walls specifically is for “ascending and descending vertical surfaces such as walls,” with the implication being the thief can do so without climbing equipment.

(PHB, pg. 28)

Climbing walls is attempted whenever needed and desired. It is assumed that the thief is successful until the mid point of the climb. At that point the dice are rolled to determine continued success. A score in excess of the adjusted base chance indicates the thief has slipped and fallen. … Success indicates that safe ascent or descent has been accomplished.

Based on a table in the DMG, an assassin should be able to climb the walls—which are likely to be around 12 feet high—at a rate of 18 feet per minute. The design notes suggest that climbing success is always checked in the midpoint. We can infer that the midpoint will be 6 feet in this case, but a much taller wall would find us checking at 9 feet, then 27 feet, then 45 feet and so on.

Disguising

(PHB, pg. 29)

Disguise can be donned in order to gain the opportunity to poison or surprise a victim — or for other reasons. … There is a base chance of 2% per day of a disguised assassin being spotted. Each concerned party (victim, henchmen, bodyguards) in proximity to the assassin will be checked for, immediately upon meeting the disguised assassin and each 24 hour period thereafter. … The chance for spotting a disguised assassin goes downward by 1% for each point below 24 of combined intelligence and wisdom of the observer concerned…

Disguise is a system leaning on the assassin’s planning and knowledge. Its full design is intricate and involved, but the relevant factors for our scenario are made plain here. There is a small chance (possibly 0%) that the assassin’s disguise will be seen through with each interaction. We can infer, from further details in the book, that modifiers are based on a combination of observer sharpness and observer familiarity. If he disguises as kitchen staff, real kitchen staff are more likely to see through it.

Notably, the clarification Gygax provides implies that if we were to stroll past Jupiter and its moons in disguise, that would require two rolls rather than ninety or more rolls.

Assassin Abilities Summary

If our assassin is 9th level, he follows the Thief Function Table (PHB, pg. 28) as if he is a 7th level thief. The overall numerical picture is:

Move Silently: 55%

Hide in Shadows: 43%

Climb Walls: 94%

Disguise: 2% base chance to be noticed, per observational party

Stealth Plan

The plan is exactly the same as before but reads quite differently:

Climb the wall from outside

Set up a rope (to be pulled down by a nearly invisible thread) to rapidly climb back up when necessary

Climb the wall down (no rope yet)

Hide until an opportune moment, particularly for the target to visit point ‘A’

Surprise backstab with a poison dagger

Mad dash to the rope

Sprint to escape the estate

Climbing up the wall takes about one minute (1). In AD&D, an assassin is implied to have a great ability in handiworks skill. Setting up a pull-rope mechanism so that he can quickly escape should be a given (2). If not, it can be likened to the assassin’s highly advanced (thief level + 2) skill at setting traps.

Climbing down the wall on the other side is another climbing attempt (3). Depending on terrain, the assassin may have to succeed at Moving Silently before he can attempt to Hide in Shadows near the gazebo (4). In all likelihood, the terrain in our scenario is grass, stone, wood, or similar—the assassin will not need to Move Silently.

If his hiding is successful, he is guaranteed surprise (5). In this case, it is more likely the assassin will opt for the Assassination Table attempt over the backstab. The details of poison are extensive in AD&D and left as additional reading for the curious.

Given the assassin’s rope setup, the guards at the estate should have limited opportunity to respond to him (6). Thereafter, his escape is granted, given no special circumstances (7).

Summary

Assuming he must climb up and down the wall, the assassin must achieve two 94% rolls. Once over the wall, he may have to attempt silent movement (55%) if the terrain is uncooperative from the supply sheds to the gazebo. The crucial attempt is establishing a hiding spot near the gazebo to guarantee surprise (43%).

If Move Silently is needed:

94% → 88% → 49% → 21%

If Move Silently is unnecessary:

94% → 88% → 38%

A lot hinges on the success of the Hide in Shadows execution. Wilson is guaranteed to die, even if the Assassination roll (around 95%) attempt fails.

Disguise Plan

The disguise plan is exactly the same as before:

Disguise as a servant

Fetch a dish from the kitchen

Poison the dish and/or drink and serve it directly to the target

Hide in the garden or near supply sheds

When an opportunity arises, climb stealthily over the wall or dash through the gate

Because the guards will, on average, have 20 total Intelligence and Wisdom, the assassin’s Disguise ability is guaranteed to fool them on the first day (the only day we need). The only time the disguise will be truly tested is against the kitchen staff who, without multiple days of exposure, are still unlikely to see through the assassin’s disguise.

Thus, steps 1) through 3) are reduced to a near certainty (again, leaving the intricacies of poison to the curious reader). Steps 4) and 5) are only necessary if something goes wrong. In an ideal scenario—a poison with onset of hours or more—the assassin could simply walk right out of the estate. But if he perceives the gate guards would be suspicious, he could hide (not in plain sight, merely laying low in an obscure, out-of-the-way area!) and wait for an opportunity to climb over the wall.

Which plan?

In the Disguise plan in RAW AD&D, our interpretation is that it’s nearly a guaranteed success. This hinges on several considerations left out for brevity. Primarily, this plan builds on previous unmentioned successes, namely scouting and spying to get the right information about the estate and what’s needed for the disguise.

The Stealth plan, by contrast, is risky. It involves the assassin leaning heavily on abilities that are available to him but not his strongest points (Move Silently and Hide in Shadows).

These conclusions, both the difficulty of executing the Stealth Plan and the near-certainty of success in the Disguise Plan, follow from assumptions the gameworld makes about assassins.

Spying in AD&D

Experienced AD&D players reading up to this point have been waiting for mention of the extensive Spying system offered up by the DMG.

Much can be explained about our scenario analysis by reading more about the assassin class:

(PHB, pg. 29)

Primary abilities of assassins which enhance their function are those of being able to speak alignment languages [other than their own!] and being able to disguise…

The secondary function of the assassin is spying.

…

Tertiary functions of assassins are the same as thieves.

Disguise is a primary ability of assassins, and their adoption of thief skills is tertiary. Their secondary function is spying, for which a generous array of systems is provided. Put briefly, we could simply resolve this entire scenario by treating it as a Spying Mission classed somewhere between Simple and Difficult. If the Spying is unsuccessful, or the spy is discovered while doing the preparatory legwork, there is a table that determines outcomes from loss of time to imprisonment to death!

In conventional play, risking a player character in this way—especially outside of a session—is unthinkable. But this design serves and elevates the gameworld, rather than the characters. It holds both practical power (the abstraction of subterfuge) and explanatory power (a second viewpoint from which to judge scenarios).

Comparing Perspectives

Thinking through the scenario using conventional-play perspective and drawing upon conventional skill system norms, we encountered ambiguities and difficulty in rewarding good planning. Conventional play’s inherent orbit around atomic-level resolution creates a two-point cycle that is difficult to escape or reverse.

A Degenerate Cycle

First, “taking action” becomes “rolling a die,” not only in the minds of the players but also in the language and expression of the rules themselves. Reducing the number of points in a proposed plan tends to reduce the number of die rolls, nearly on a one-to-one basis! The gain in success chance for this is the opposite of the intended effect of planning; a well-rounded plan of action should make things easier, more efficient, and more robust even if the plan doesn’t play out precisely as imagined.

Second, navigating gameworld scenarios on the atomic level is most natural through improvisation—stepping through each moment “live”—rather than having two distinct ‘planning’ and ‘execution’ stages. The effect on planning is even more intensive here, removing it from sight and mind as player mastery increases; planning becomes execution, and execution stands in for planning.

These two points reinforce one another—and one leads directly to the next, causing a feedback loop in player analysis that results in atomic-level thinking across the entire game system. When a plan and its execution are thus intertwined, it becomes necessary to model atomic-level action. And when it is necessary to retreat to atomic-level questions, that implies a resolution step for each such action—otherwise there would be no need to break out the microscope.

But how did this happen? How does this pattern take hold?

Imitation is a form of Flattening

It would not be a stretch to say that 95% (or more) of the design that goes into conventional skill systems descends directly from the thief and assassin abilities in AD&D.

The difference is that later systems (including supposed successor AD&D 2E) are copying the surface-level qualities of the thief abilities while fumbling their natural place in the game’s hierarchy3.

Reducing a game into a mere Character System

The introduction to “Nonweapon Proficiencies” in 2E unintentionally sums it up well:

(AD&D 2nd Edition, pg. 52, Nonweapon Proficiencies)

A player character is more than a collection of combat modifiers.

Indeed, now a player character is a collection of combat modifiers and non-combat modifiers—the full spectrum of play quantified at our fingertips! Even without deep analysis, this collapse of rich campaign interaction into myopic character focus elicits suspicion.

In a TTRPG, action and reasoning should flow through the filter of the gameworld’s assumptions. The gameworld has its own natural laws, boundaries, and idiomatic patterns which inform the efficacy of different actions in different situations.

But the conventional-play approach makes the gameworld subservient to marks on our character sheet! This is a subtle but crucial distinction, and the gap in mindset multiplies across the entire system. We are no longer carefully plugging our character into the gameworld but instead treating the gameworld as a mere firmware update for our cool character. This sets both designer and player into a mindset where major game systems that aren’t represented on a character sheet cease to exist.

Even in earlier examples of this mistake, we can see the failures of this thinking. The designers explain their mindset behind the AD&D 2nd Edition skill system:

(AD&D 2nd Edition, pg. 53, Nonweapon Proficiencies)

For example, Delsenora the mage slips at the edge of a steep riverbank and tumbles into the water. The current sweeps her into the middle of the river. To escape, she must swim to safety. But does Delsenora know how to swim?

This is fundamentally no different from the unserious character narcissism that brought us the Combat Wheelchair. “But can this adventurer walk without assistance?” Instead of becoming a target for mockery on then-inexistent social media, the bell-tone of this question rings across the whole of the game. Without its deserved pushback, this idea becomes one of the foundational pillars of the character system.

Anything that a character might attempt to do is a question posed to a die; the gameworld grows more and more distant until it becomes a backdrop in our dice game. The ‘D20 System’ encapsulates this setting-agnostic pattern perfectly, reducing each of its games to a mere character system.

It is unnecessary to read the rule book extensively to understand what a “Stealth Check” and “Disguise Check” are in a conventional skill system. By comparison, we had to read the assassin and thief abilities very closely, lest our assumptions lead us astray. Though seeming like an advantage, this is indicative of our character actions becoming disconnected from the workings of the gameworld.

Elevating the Gameworld

By contrast, AD&D’s systems are constructed to answer questions about actions that each particular class would logically pursue—the full scope of questions; not just those whose answers are “Success” or “Failure”!

Deeper examination shows it was not meant to be a generic, universal resolution system. Instead, each class ability is given a detailed description based on its role in the gameworld—the designer is telling us about the game’s Hierarchy while he imposes it on the character system.

Having set the two side by side, setting-agnostic character builders vs. a real TTRPG, we can grasp what ideal TTRPG play is like—and then judge a resolution system on how well its structure supports that play.

1. Absorption: Players learn the expectations the gameworld places on their character’s class.

2. Alignment: Players align their thinking and planning with the behaviors intrinsic to their class.

Not only does this result in higher player understanding of the game as a whole, but it directly improves the rate at which they progress with their class. The player levels up as the character levels up. AD&D accomplishes this, for example, by adjusting earned XP based on class-alignment performance.

3. Agency: While attempting to play out the plans and thinking adopted by learning their class, the players are posing situations to the game. The game “answers” these situations with its resolution systems.

Game systems provide anchors of certainty on which to base uncertain propositions. The more strongly player expertise is rooted in gameworld knowledge, the more leverage their character has to affect campaign canon.

In stark contrast to this pattern of ideal play, players in a conventionally run game only need to be good at deploying skill lists and choosing bigger numbers to ensure success. In ideal play, character progression will require and reinforce player growth.

Structural Integrity

In a conventional skill system, the assassin is merely someone who is good at particular kinds of dice rolls. But AD&D’s resolution systems show a game-wide architecture that not only suggests the nature of the world but forms the identity of the assassin through its design.

The analysis of a scenario with AD&D resolution shows us a game interested in answering questions about things that could happen. Elevating the gameworld above the characters that inhabit it is the only way to achieve the richness it presents.

In conventional play, ability resolution exists as a mere abstraction, a way to impose player will into the campaign canon—it supports the formation of abstract archetypes. This inherently agnostic view of the gameworld is sharply contrasted by the care with which AD&D weaves its classes into its implied setting until it becomes difficult to separate them.

Macroscopically, the architecture that our resolution systems create can either elevate the gameworld above the pieces it contains or lead to the dissolution of proper TTRPG hierarchies. But on the microscopic level, there are other issues: dice-level interpretation, limitations on dice techniques (asymptotic probability decay), and others. We will leave these to be addressed in Part 2.

Meanwhile, we should ask ourselves whether the structure of resolution in our games is a mere character system or something that describes and supports the gameworld—the font from which all richness flows.

Thank you for your readership! Primeval Patterns thrives on the basis of the sincere interest and support of hobbyists like you.

Liked the article? Some other interesting things:

Follow the author on twitter.

Check out BMD, a far-future wargame-infused TTRPG about slaughtering aliens. See the latest intel on the war.

Think carefully when designing or using skill systems!

Understand starting an ACKS campaign from scratch.

With work, we can achieve TTRPG Supremacy!

If you are a true fanatic, take the oath of battle and become a paid subscriber here on Substack. This directly supports the war effort (and the development of BMD plus the design research on this blog.)

BONUS: paid subscribers can read extensive BMD development blogs and are guaranteed a PDF copy on BMD’s release!

Atomic-level resolution systems are incapable of handling mass-action; they teach players to think in a way that deems large-scale events impossible to resolve, leading to excessive handwaving or abstraction.

See a substantial discussion of the flaws of conventional skill systems, including this ambiguity of interpretation.